Stagecoach

Stagecoach (1966)

The full movie of “Stagecoach” is now available on YouTube! This movie was one of the first big motion pictures Alex Cord made. The original was a classic movie starring John Wayne and Alex starred in the first remake. “Stagecoach” had an all-star cast including Bing Crosby, Red Buttons and many more!

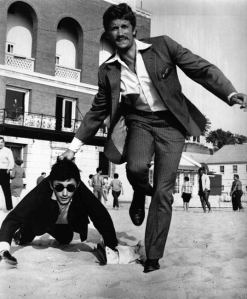

Rare Footage! Behind The Scenes of Stagecoach!

A rare video has found it’s way onto YouTube! Rare behind-the-scenes footage from the movie Stagecoach. It’s amazing what people dig up to put on that website. Enjoy!

Rebellious Romeo Alex Cord

AN ARTICLE FROM A DELL PUBLICATION MOVIE MAGAZINE FROM THE MID-60S BY LAURA POMEROY

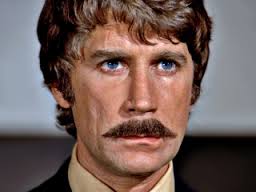

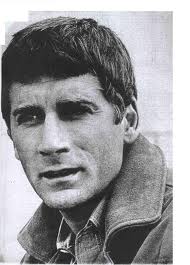

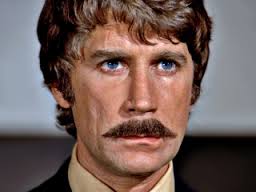

It was the first day of shooting on STAGECOACH and the two young stars playing the sweethearts in the film were about to be introduced. Ann-Margret, one of the sexiest young actresses in films, and Alex Cord, tall, rangy, one of the most exciting new actors to hit Hollywood in years, were about to meet for the first time.

It was the first day of shooting on STAGECOACH and the two young stars playing the sweethearts in the film were about to be introduced. Ann-Margret, one of the sexiest young actresses in films, and Alex Cord, tall, rangy, one of the most exciting new actors to hit Hollywood in years, were about to meet for the first time.

Both these young stars radiate vibrant sex appeal, which was one of the reasons they were selected for this remake of the lusty movie which years ago had made a star of John Wayne. As Alex sauntered over to meet Ann-Margret, some observers on the set stopped to see what the impact would be, expecting “Wow.”

Instead, as one of them said later, the meeting was decidedly chilly. “Enough to put a frost on a Palm Springs pool,” the observer reported. “Alex was particulary unimpressed; he just extended his hand, mumbled a few words to Ann-Margret, then walked away.”

When I caught up with Alex at a hoedown given by 20th Century-Fox to celebrate the start of the film, I asked him if it was true that his reaction to sexy Annie was on the chilly side. Very few healthy males remain unimpressed upon meeting her.

Alex, dressed in the Western costume and broad-brimmed hat he wears in the picture, smiled sardonically. “The kind of girl who seems to impress every other man manages to leave me cold,” he said. “I don’t go for actresses — they’re too self-centered. The raving beauties like Ann-Margret and Elizabeth Taylor don’t raise my pulse. They’re too studied. They’re great for other men, but I don’t go for calculated beauty of studied sex. And that’s usually what you get with an actress. Her whole life revolves around her face, the way her hair is done and the clothes she wears. They all look alike. Also, they’re always looking around, when you take them out, to see if anyone’s noticing them. Hollywood actresses are so determined to get there that, notwithstanding their beauty, they have a certain masculinity. They crowd a guy out.

“I’m attracted to very feminine girls,” Alex went on, “the kind of girl who looks as though she needs help getting across the street. I like a girl who is not conventionally pretty, who doesn’t think of herself all the time. That leaves out actresses in my personal life.”

Just then, a beautiful girl with dark hair, wide, brown eyes and willowy figure walked over to Alex. He leaned over and kissed her warmly. I recognized the girl as Anjanette Comer, a young actress causing quite a flurry in Hollywood since her appearance in THE LOVED ONE. There was no mistaking the affection between them.

“Are you serious about Anjanette?” I asked.

Alex grinned. “Crazy about her.”

“But this doesn’t make sense,” I said. “First you claim you can’t stand actresses. They bore you, annoy you; are trite, bossy, unfeminine. You said you hate to date one. And now you admit to being in love with one of the most dedicated young actresses in town.”

Alex put his arm around Anjanette’s shoulder. “Whoever said I take my own advice? Sure, I don’t go for actresses. And yes, I do go for Anjanette. She’s my girl. But she’s different.”

If this sounds confusing, then it’s just a tip-off to the free-wheeling personality of a young actor who intrigues Hollywood because he is different.

The rebel in Alex is reflected in his face, which is lean, sharp and intense; in his manner, which is devil-may-care; in his clothes, which are casual; in his attitude, which is non-conformist.

“I had to learn to think for myself,” he explained, “because life tossed me so many curves. When I was a kid in New York, I came down with polio. Everyone was afraid I’d walk with a cane for the rest of my life. But I knew I’d walk again. I also knew I’d have to fight to make it.

“When I came out of the hospital, I wheedled my parents into letting me go to a ranch in Wyoming, where they had some friends. I was only twelve then, but I knew I had to go there. At first my parents were afraid to let me to be on my own. How could they send a half-paralyzed, skinny kid to a ranch where he’d have to compete with husky cowpunchers?

“Finally, I got them to let me go. I wasn’t afraid. I knew I’d make it. And I did. I rode horses and lived in the outdoors. The exercise and outdoor life restored most of my muscles. I became a good rodeo rider and decided this would be my life.

“When I was 19, just as I was doing great as a cowboy, a bull gored me. At the hospital, the doctors thought I was going to die. They operated on me and removed my spleen. I had to lie in bed for months. I had been used to a physical life; now I had to rely on my intellect to see me through.

“I began to read books and plays, and I found a whole new world. I particularly loved the plays, finding myself mentally acting out various characters. That’s how I first got the thought of becoming an actor. It never would have occurred to me if I’d continued as a rodeo rider. It was only when I was stopped by this accident that my life took this turn.

“When I recovered, I went to New York to become an actor. I did little plays, stock, anything I could get around Broadway. It wasn’t easy. I had to work on a construction gang to earn enough money to continue with acting, and I went hungry plenty of times. But I was stimulated by the urge to be an actor. I had finally discovered my goal in life.

“Eventually, with the experience I piled up, I finally received the Hollywood call and did my first starring role in SYNANON. STAGECOACH is a big break, and yet a challenge. I can only hope they don’t keep comparing me with John Wayne, who originally did this role. He is a film immortal, and I want to be judged as myself.”

Hollywood had a chance to judge Alex when he first came to town. Instead of the pretty, young actresses who are so popular with newly-arrived leading men, his steady date, to everyone’s surprise, was Shelley Winters.

Alex let Hollywood speculate about the “romance.” Laughing, he explained to me, “Shelley and I are old friends. We met in New York years ago, when I was learning to act and I saw her in A HATFUL OF RAIN on the stage. I went backstage to tell her how much I liked her in the play. We’ve kept up a friendship ever since.

“When we saw each other here, everyone thought it was a red-hot romance. Shelley and I laughed about it. We just let them guess and talk. I love being with Shelley; she’s a remarkable person, one of the most stimulating women I’ve ever known. And she’s also very kind. She’s done more to help me as an actor than anyone else has. But she’s also all woman. It wasn’t fair to her to have all the cracks made about a big star like her going with an actor younger than she. That’s why I’m explaining it here.

“The only girl who’s meant anything to me is Anjanette. A mutual friend introduced us, a blind date, so we expected to hate each other. She’s a strong-minded individual; so am I. But instead of fighting the first night, we fell in love. And that’s the way it’s been ever since.

“One of the things I like about her is that she cares about me. Sounds conceited, but that’s not the point. I’m speaking as a man — and a man loves to feel that a woman cares about him. Anjanette is feminine enough to show that she cares for the man she’s with. Most Hollywood actresses care only for themselves.

“But here we go again. I never thought I could be so gone on an actress; but I am, for this particular actress. But then, I never thought I’d be doing a lot of things I’m doing now.”

And that’s Alex Cord for you — an unpredictable man and a rebellious Romeo.

DON’T FORGET TO PICK UP A COPY OF THE LATEST ALEX CORD NOVEL “DAYS OF THE HARBINGER” TO FIND OUT MORE ABOUT THE REAL ALEX… IF YOU WANT TO KNOW ALEX CORD HERE’S YOUR CHANCE! HOW CLOSE IS ALEX TO JOHNNY GRANT?

Related articles

- Bethenny Frankel Made ‘Laughable’ $400 Offer To Ex-Costar Alex McCord To Appear On New York Housewives Talk Show Reunion (radaronline.com)

- How Far Would You Go for Your Family: Prisoners Reivew (goodsweep586.wordpress.com)

- HOUSEWIVES NEWS: SH **Exclusive** Melissa Gorga’s Secret TATTOO!!…Jill Zarin “Waitin’ For Personal Call” From BFrankel!…Alex McCord RSVP’d “NO” To BFrankel… What’s Silex Doin’ Now??… “BrownstoneBrooklyn” And “ALuxe” Deluded Dreams… (stoopidhousewives.com)

- Why did Alex McCord Turn Down a Spot on “Bethenny”? (realmrhousewife.wordpress.com)

- The 15 Worst Celebrity Magazine Photoshop Fails (businessinsider.com)

- Alex McCord Discusses A Possible ‘RHONY’ Reunion (celebs.gather.com)

- Alex McCord Gives Advice to Gretchen Rossi and Alexis Bellino on How to Handle Firing from ‘Real Housewives’ (celebs.gather.com)

- Hottest Articles on BWW from Wednesday, Oct. 9 (broadwayworld.com)

- Alex McCord Hints That Someone Leaked Her Conversation With Bethenny Frankel? (celebs.gather.com)

Alex Cord On Horses, Acting and Why He Is Saving Money…

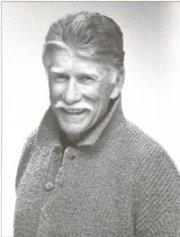

Movie star and bestselling author Alex Cord is on the interview trail again with incoming interviews from Simon Duringer and Fiona Mcvie. It’s only natural for Alex to be interviewing as the internet has been devoid of his presence for a long time. Alex the man looks after his privacy but loves his fans. He enjoys writing, reading and rarely catches his old movies. As an interviewee he is the perfect gentleman with patience a-plenty. Alex will be at the “Spirit of the Cowboy” festival later this week to meet with fans, old friends and some new ones. For those of you who can’t attend he is also throwing a Facebook party! Come and join his event to ask questions, get autographs and meet with other Cord fans the world over. Fans keep telling Alex that the world needs more of his presence so here we have an interview from the younger Cord… Enjoy!

Alex Cord is one of the most respected horsemen in Hollywood. He spends most of his spare time at the Los Angeles Equestrian Center, training and schooling his own polo horses. He is a member of a celebrity polo team that includes William DeVane, Jameson Parker, Doug Sheehan, Pamela Sue Martin and Stefanie Powers. The team performs frequently in L.A. and also travels all over the United States, putting on celebrity matches for various charities. They have raised more than $2-1/2 million.

Alex Cord is one of the most respected horsemen in Hollywood. He spends most of his spare time at the Los Angeles Equestrian Center, training and schooling his own polo horses. He is a member of a celebrity polo team that includes William DeVane, Jameson Parker, Doug Sheehan, Pamela Sue Martin and Stefanie Powers. The team performs frequently in L.A. and also travels all over the United States, putting on celebrity matches for various charities. They have raised more than $2-1/2 million.

When he’s not on horseback, Alex makes a living as an actor. He’s been in many television series, one of which is Airwolf, in which Alex has a recurring role. His feature movie credits include The Brotherhood, with Kirk Douglas and Alex had the leading role in the 1966 remake of the John Wayne classic, Stagecoach. He has just finished a movie called Street Asylum, with G. Gordon Liddy. Cord is also a published novelist and has sold several screenplays.

Horses have been a lifelong interest for Cord. He has recently gotten involved in cutting as well as polo. In fact, Alex is an all-around horseman who has ridden more kinds of horses (all over the world) than most horsemen ever will. He enjoys all kinds of riding, and is something of an authority on general horsemanship.

Alex says, “As an actor, I’ve had the opportunity to do a great deal of traveling — in this country and around the world. I’ve ridden with horsemen everywhere, and found that most people who are involved with horses get stuck in their own personal discipline. They pride themselves on that particular way of riding and disdain everything else.

“The hunter/jumper people are snobby about cowboys, polo players think team ropers are wasting their time, cutting horse people think cutting is the only thing in the world worth doing horseback, and dressage people are in their own narrow world. Each one thinks his activity is the only way to use a horse.

“I’m interested in all of it. I’ve poked my nose everywhere I can. I ask a lot of questions, and I think I’ve learned something from every good horseman I’ve ever met — and that includes some darn good horsewomen. I’ve tried almost every kind of competitive riding there is, and I’ve learned something about horses and myself every step of the way. The horse can be a great teacher, if one will only listen.”

Cord’s earliest dreams were to become a jockey. He was born right near Belmont Park in New York. As a school-age child, he’d leave for school an hour early and ride his bicycle to the racetrack. “I’d hide the bike in somebody’s hedge,” says Alex. “I’d climb the fence and hide in the brush where I could watch the horses being worked. All my heroes were little guys who rode fast horses.”

There were lots of horses on Long Island in those days, and young Alex took every opportunity to ride. There were polo fields and rental stables. On Saturdays, he took care of horses at the stables so they’d let him ride. He says, “I’d take people out on trail rides, and, in the summers, I worked at the racetrack, walking hots or doing anything else they’d let me do. I even got to excercise some race horses.”

Eventually, Alex realized that he was growing too big to ride race horses professionally, so he started to ride in rodeos. There were a few small rodeos in the area, and a rodeo producer names Colonel Jim Eskew had a place in Waverly, New York. “I worked with him and rode broncs and bulls in his rodeos,” says Alex. “I did okay on bulls and bareback horses, but I could never hit the right lick on saddle broncs. My heroes were Casey Tibbs, Jim Shoulders, the Linderman brothers. And I’m proud to say that Casey is still a good and close friend.”

About that time, Alex dropped out of school and bummed around the West for five or six years, mostly riding in rodeos. He began to realize, though, that he needed to finish his education, so he went back to New York, finished high school, and entered college. It was there that he first became interested in theater and acting.

“It completely changed my focus in life,” says Alex, “and for a period of about 10 years, I stopped riding horses. I lived in Greenwich Village in New York, studied acting, hung out in coffee houses, and worked in the theater doing plays by Tennessee Williams, Samuel Beckett, and William Shakespeare.”

After 10 years in theater, Hollywood called and Alex began to work in films. “That’s when I began to get on a horse again.”

But things changed again in the late ’60s. Cord became disenchanted with Hollywood, and he moved north to the Carmel Valley, where he could enjoy the rural life. “I leased 200 acres,” he explains, “and started buying and training Quarter Horses. It was like rediscovering myself. I was living out in the boonies, I was alone, and once again horses became my life. The passion was stronger than it had ever been.

“There was a man there named Bill Lambert, a rancher who was a hell of a horseman. He showed me a lot of cowboy stuff, good things. I learned a lot from him.”

Alex spent five years there, in a state of semi-retirement, working with horses and writing a novel. The novel got published at about the time the land owner decided he wanted the ranch back, so Alex returned to Hollywood to do publicity on the book.

“But then I knew that I had to do something to keep up the riding,” says Alex. “One kind of riding I had never done was English, and I had never had any formal training as a rider. I thought I might be able to learn something new, so I found a woman who was a good trainer with hunter/jumper people, and I started taking lessons. I rode a lot of jumpers, and I learned a hell of a lot from her. And right about then I think I decided to be the best all-around horseman I could.”

Alex has been dedicated to achieving that lofty goal ever since. He has taken every opportunity to ride, no matter what kind of horse or riding is involved. He mentions some of the things he’s tried. “I studied dressage for two years. I’ve ridden hunters and jumpers and was a whipper-in with a fox-hunting club for five years. I compete as a roper, with varying degrees of success, and I’m getting real good with cutting horses — I’ve been working with Leon Harrel and Bobby Hunt and Jerry Lucas. (Last December 4, Alex won the celebrity cutting at the NCHA Futurity in Forth Worth on Leon Harrel’s mare Swingin’ Tari.) I’ve ridden in amateur steeplechase races, and I’ve even ridden Andalusians, doing airs above the ground. When I was a kid, I even tried a bit of trick riding, with Rex Rossie. Right now, I’m serious about polo. About the only thing I haven’t at least tried to do is ride a hundred-mile endurance race.”

Alex explains that anytime he is around horse people, he keeps his eyes and ears open, ready to learn anything that he can. He says, “I’m helping my assistant, Wendy Rothwell, to ride and to school my horses. The other day, I asked a professional how to correct a little problem one of my horses had. That, to me, is how you get to be a good horseman. You keep yourself open to anything.”

Cord’s acquaintances consider him to be a highly knowledgeable horseman. Alex says he can point to no source more than any other for the bulk of his knowledge.

“Absolutely, without a doubt, the ones who have taught me the most are the cowboys I have known. So often, in the larger part of the horse world, cowboys are not given nearly enough credit for their skill with horses. In fact, people will use the phrase, ‘Don’t cowboy that horse around,’ in a derogatory fashion. I get a little annoyed with that because when you watch a man like Leon Harrel or John Lyons or Ray Hunt or Tom Dorrance, you can see that they are highly skilled men with great sensitivity who know how to get a superior performance from a horse.”

In one instance, Alex was able to pass along a bit of his “cowboy” education to a professional rider. A friend of his had represented Puerto Rico in dressage in the 1984 Olympics. She had lived 10 years in Germany, riding the big German warmbloods and learning from the German riding masters. Alex was helping her work dressage hroses at teh Equestrian Center, and she was teaching him a great deal.

“She was an Olympian,” he recalls. “I never dared to presume I could give her any advice, but one day she complained about a big horse she was riding. ‘He’s so stiff on the right, he’s pulling my arm out of the socket.’ The horse was a monster, a 17-hand Holsteiner.

“I remember looking over my shoulder to see if any of those other ‘velvet heads’ were around, and then I said, ‘Have you ever tried tying his head to his tail?’

“She had no idea what I was talking about, so I tied the horse’s head around to the right, and we watched him for about 20 minutes. She was amazed. She’d never seen it before. When she got back on the horse, he turned to the right, just like she’d been trying to get him to do. She said, ‘I don’t believe this. I’ve been working him for four days and haven’t been able to get him to soften up on that side. He’s a different horse!’

“I said, ‘I learned that from an old cowboy one time.’

“That incident,” says Alex, “just goes to prove that you can learn from anybody. She was an Olympian, and she learned from me.”

Cord says that another way he learns is by teaching. “Wendy has been working with me a couple years now. I tell her stuff, but when I do, I’m reinforcing what I know. I’ll watch her ride, and when she makes a mistake I correct her and I learn, too.”

You would expect that a man like Cord, who has had so much experience on so many kinds of horses, would have an opinion about what breed he likes best. Says Alex, “Different breeds perform well in certain areas. If I was as seriously involved in cutting as I am in polo, I know the Quarter Horse would be it. Anyone who tries cutting on anything else is wasting his time.

“But apart from that or working cattle, to me, the Thoroughbred is the horse. They’re harder to train, they’re more temperamental, hot-blooded, liable to jump out of their skin, but the thing I love about them is that they’ve got that spirit, that flash of movement, that lightness. The Thoroughbred sweeps over the ground, real light and buoyant. That’s what I like. For polo, it is almost essential that you ride a Thoroughbred. You are going to get blown away if you are on anything else.”

Polo is a subject that Alex is enthusiastic about, and he speaks almost reverently about polo horses. “Nothing but the Thoroughbred has the speed or the stamina for the game. An Arabian has endurance, but he runs like he’s tied to a post. A Quarter Horse has a good handle on him and is quick for a short distance, but he runs out of gas in 2-1/2 minutes. A polo pony has to gallop non-stop for an average of 10 minutes. When he does stop, it is a hard stop, and he has to turn left or right and jump out with the same intensity — whether he’s going to gallop 300 yards or 15 feet. Then, suddenly, the ball changes direction and you’re on his face again, asking for the stop and another start.

“That’s one thing few horsemen understand about polo. In every other equestrian sport, the horse gets to learn a pattern of behavior. A jumper knows he’s expected to jump. He can relax between jumps. A race horse knows what he has to do, the cutting horse has a pattern of activity, the calf horse rates the calf and knows about how every time out will be.

“But the polo horse never gets a chance to learn a pattern of behavior. He can’t learn to chase the ball, because there are times when the rider can see that the ball is about to change directions, so he turns the horse before the direction change, in anticipation of the shot. The horse is always at the rider’s will. That’s why polo ponies are wired all the time. They can never rest. They never know what they’ll be asked to do next or when it will happen. They have to run like blazes and stop at any time.

“And they’re getting bumped all the time by other horses. It’s a tough sport, and it takes a special horse to be able to handle it. Particularly, the mental stress.

“Playing polo is a bit of a dichotomy for me. I’m such a horse lover. I am a subtle rider. I’m skilled. I know how to ride a horse on a shoestring and have him as light as he can be. But when I’m in that game, there are lots of times when I’ve got to sit down, haul back, pick him up, spin him over his hocks, and spur him on again. There’s no way around it. That’s the nature of the game. My hat is off to the polo ponies. I think there ought to be statues of them everywhere.”

Like many westerners, Cord has a kind of cowboy outlook on things. He speaks of how much he would like to have lived in an earlier time. “I’d like to see us go back to an age before the internal combustion engine. I could live very well without cars. If it were up to me, I’d rip up all the concrete everywhere and drive a horse and buggy. Even though I was born on Long Island, at heart I’m a cowboy. That’s the way I like to think of myself. I’m all for burning three-piece suits and bringing back the jeans and the big hats.

“My dream is to make enough money that I can turn to writing more than acting. Then, I’d move to Texas or Arizona and have a place of my own. I was never happier than when I was on that ranch in the Carmel Valley.”

It is the world of horses that brings Alex Cord his greatest pleasures, because being a good horseman is a continuous challenge. Alex says, “I always say that it is a lifelong pursuit for a perfection that you can never achieve. If anyone tells me he or she is bored, I tell that person to get involved with horses. You’ll never be bored a minute in your life. There is no time for it. There is something new to learn all the time.”

DON’T FORGET to catch a copy of Alex’s latest bestselling novel “Days of the Harbinger.” If you want to know Alex… This book may let you into his very, very private thoughts.

Alex Cord Goes On A Safari…

(This article was published in the October 1969 edition of SAGA Magazine.)

You need more than bullets for buffs. . . . you need luck, a sharp shooting eye, a steady hand — and ice water in your veins. Ask movie star Alex Cord, who, from his own terrifying experiences, will tell you that the Cape buffalo is the most unpredictable, vengeful, ill-tempered and cunning animal in Africa. He should know, he’s been charged by a pair of these treacherous beasts within five minutes of each other — DROPPING ONE LITERALLY AT HIS FEET!

You need more than bullets for buffs. . . . you need luck, a sharp shooting eye, a steady hand — and ice water in your veins. Ask movie star Alex Cord, who, from his own terrifying experiences, will tell you that the Cape buffalo is the most unpredictable, vengeful, ill-tempered and cunning animal in Africa. He should know, he’s been charged by a pair of these treacherous beasts within five minutes of each other — DROPPING ONE LITERALLY AT HIS FEET!

Tracking a Cape Buffalo in the lengthening bush shadows, cinema-television star Alex Cord and a Kenya white hunter, John Fletcher, were studying the spoor when a thicket, 40 yards ahead of them, exploded and three quarters of a ton of raging buffalo pounded toward them, short head lowered, massive horns out thrust above large fringed ears like deadly Maasai spears.

Aiming his double-barreled Rigby .470 at the tip of the buff’s nose two inches above the slime-dripping nostrils, Cord squeezed the trigger.

The heavy slug checked the buffalo’s maddened charge. It raised a dust cloud in its death slide into the dry ground.

“I knew I was going to kill that buff with one bullet before I fired,” Alex recalled later. “It wasn’t overconfidence, prescience — nothing like that. It was something I can’t realy explain. Every once in a while a hunter has the feeling he’s about to score a perfect shot. I had the feeling then. The bullet that killed the buff came straight from my heart.

“Our bearer and the skinner were in the Land Rover some distance behind us when Johnny and I began to walk toward the dead buff.

“We were about 25 yards from it when a second buff erupted from a thicket 60 yards away where it had been standing motionless, watching us.

“This one, even bigger than the first, caught us completely by surprise.

“I brought up the Rigby and Johnny yelled, “Wait!”

“Johnny is young in years for a professional — about my own age. But he’s one of the top pros in Kenya. I’d hunted with him before and had absolute confidence in his judgment. So I waited.

“The buff came on like an express train. The gap between us narrowed to 30 yards, to 20.

“There was a scarce 15 yards between us when Johnny called out again.

“I triggered off a frontal brain shot and dropped the buff literally at my feet.

“Pretty close,” I said to Johnny and wiped the beads of sweat from my forehead.

“Johnny looked down at the buff, then at me and grinned.

“You know John Cook, the hunter at the Treetops Hotel? One time a buff came at him from behind a big boulder. He got off one shot. Hit the beast in the throat and blew a hole in him you could see through but the buff kept coming. When he dropped dead it was on not in front of the toe of Cook’s left boot. That’s what I’d call pretty close.”

In his four African safaris Alex Cord has had several narrow escapes from death. Danger, however, is by no means unusual to him for he, himself, is a most unusual guy and his rocket-like rise to movie stardom in The Brotherhood with Kirk Douglas represents only one facet of his many interests.

Born in New York City, Alex was stricken with polio at the age of 12 and his determination to regain the use of a badly crippled leg took him to a Wyoming ranch where he grew up in the outdoors. Doctors recommended riding as a therapeutic exercise. Not only did it prove helpful to his copmlete recovery but by the time he was 16 he was so expert in the saddle that he became a professional rodeo rider, competing in contests throughout the country.

Like other top riders it was inevitable that he took a number of severe falls and broke several bones. One of his worst injuries occurred when he was thrown from a wildly bucking bronc in New York’s Madison Square Garden. After being hospitalized for several weeks he decided there was more to life than his world of horses and steers.

As a youngster he had made himself a promise to go to college. Now he enrolled in New York University, financing himself with a part-time and summer job in the construction business. It was a decision he has never regretted.

“The biggest turning point in my life came in 1957,” he says. “It’s like you start out along a single trail and someplace along the way you come to a fork. Take one fork and you move on in a certain direction, take the other and you’re heading toward another destination.

come to a fork. Take one fork and you move on in a certain direction, take the other and you’re heading toward another destination.

“One night I saw Sir Lawrence Olivier’s film version of Richard III, and his performance so inspired me that I resolved to become an actor.”

Alex enrolled in the Shakespeare Academy at Stratford, Conn. He applied himself with the same characteristic intensity with which he had conquered polio and rodeo broncs. He studied at New York’s Actors Studio and played summer stock in 1959 and 1960.

In 1961, he toured with the Stratford group’s productions of Shakespeare and went to Hollywood for several television appearances.

British stage producer Oscar Lewenstein was looking for a leading man to play opposite Siobhan McKenna in Play With A Tiger. He saw the young actor’s work and cast him in the part.

Not only was the play a success, but Alex was nominated for the London Critics Award. After more Hollywood television appearances, he returned to England to score again in The Rose Tattoo on the stage, and in dramatic performances on the BBC-TV.

Alex was vacationing in Arizona, keeping in condition by roping and breaking wild horses, when producer-director Richard Quine asked him to test for a role in Synanon, a drama of the struggle against narcotics addiction. Quine liked the result so well that he cast Cord in a starring role in the picture and signed him to a non-exclusive contract for six additional films.

Six feet tall, a lean and muscle-tough 160 pounds, dark complexioned and gray-eyed, Alex was ruggedly handsome with nothing pretty-boy about him. When he was spotted by movie producer Martin Rackin he was cast for the role of the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, the same part that luanched John Wayne’s rise to stardom years before.

Alex has been doing a considerable amount of reading about Africa and the more he read about the continent and big game hunting the more he yearned to see the country. He was also a crack shot, having progressed from a .22 as a 12-year-old to a 12 gauge shotgun, a .30-30 lever action and a 30.06.

His opportunity came during a break between pictures and he went off to Africa. His first safari was more in the nature of a sight-seeing tour of the entire continent.

“I did the whole bit from Johannesburg, South Africa, right on up to the northern end and the more I saw, the more I liked,” he said. “My real love affair was with Kenya and I spent more time there than anywhere else.

“I went on safari and bagged some game: a zebra, wildebeest, and other plains animals. There’s a sporting element to hunting game like that. Such animals are comparatively fast, the hunter must be a fairly good shot and the game gets a decent break.

“I refused to hunt leopard. Sure it has a reputation for being fierce and dangerous, but it’s not my idea of a game animal.

“Leopards are suckers for walk-in traps into which they are lured by either live or dead bait, such as wildebeest, antelope, goat or wild pig.

“With the demand for leopard skins being what it is, a good many of the spotted cats are caught illicitly in steel traps — mostly of American manufacture, I should point out — and the species faces extinction.

“When a visiting hunter wants to shoot a leopard the safari leader puts him on a platform in a tree. Live bait is staked, or a carcass placed in a small clearing.

“The leopard is a night prowler and the hunter waits for it on the platform when darkness sets in. If the cat puts in an appearance it usually offers a perfect, and stationary shot to the hunter who knows the distance between platform and bait to the foot and just pulls the trigger. In my book that isn’t hunting, but slaughter.”

While in Kenya, Alex became acquainted with several pros, like John Fletcher. Another was the famous bush veteran, game warden Maj. Evelyn Wood Temple-Boreham, one of the dwindling number of European administrators in Kenya.

Temple-Boreham fought the deadly Mau-Mau terrorists back in the 1950s and now supervises the poacher-endangered gamelands as senior warden for all southwest Kenya.

“Animals have killed 21 people — all Masai tribesmen — in my jurisdiction during the past three years,” he told Alex. “Cape buffalo got a number of them. They’re treacherous beasts. I’ve known them to hide in brush by a water hole, wait for native women to come and fill their jars, then rip the women up the back as they start home.”

John Fletcher and another white hunter, Henry Poolman, agreed that the Cape buffalo was the most dangerous animal in all of Africa.

I decided then that some day I’d return to Kenya and hunt buff with Johnny,” said Alex. “But let me tell you the tragic story of Henry Poolman.

“He was about 32, a big guy, I’d say 230 pounds. He had a terrible scar on his leg where he’d been bitten by a lion. He got it when the lion suddenly attacked him and he jammed his knee into his mouth, which was better than having his head chewed off and also gave him a chance to kill the lion. It takes plenty of guts to do anything like that, and Henry was one gutsy guy.

“Last year he was on safari when a lion suddenly sprang out of cover between him and his client. The cat attacked the client from behind, knocked him to the ground and grabbed his shoulder in its jaws, getting set to make the kill.

“Henry reacted fast. He pulled his knife and jumped on the lion’s back. He was about to plunge the blade into the snarling cat when his gun bearer, who had stopped several yards behind him, fired. The bullet killed Henry, not the lion . . .”

“Henry reacted fast. He pulled his knife and jumped on the lion’s back. He was about to plunge the blade into the snarling cat when his gun bearer, who had stopped several yards behind him, fired. The bullet killed Henry, not the lion . . .”

Kenya was an irresistible magnet which drew Alex Cord back repeatedly between pictures and television specials he made, including The Scorpio Letters for MGM, The Lady Is My Wife for Bob Hope,A Minute To Pray, A Second To Die for Selmur Productions, and the tremendously successful The Brotherhood in which he co-starred with Kirk Douglas.

On one safari with John Fletcher, after being attacked by two Cape buffalo in less than five minutes, he “joined the club” of sportsmen who regard the buff as the most dangerous big game animal in Africa.

“A buff will not flinch from a bullet the way a rhino or an elephant sometimes does,” Alex explains. “Even if you hit him with the heaviest gun you can carry, say a .500 double Jeffery, he’ll still come right at you unless your shot is fatal.

“He’s cunning, too. Wound him and in mid-charge he may double back. But it can be fata error to interpret this as retreat. The wounded buff may circle widely through the brush or high grass and attack again from another quarter. Or he may decide to lie in ambush beside his trail for the hunter that wounded him.

“In Nairobi bars, where big game hunting ‘advice’ is dispensed as frequently as gin and bitters, they say that a wounded buff will wait as close to the trail as there is concealment so that his second charge will be short as possible. They also say that he’ll always hide on the same side of the spoor from which he approached it.

“Neither is true. The buff may lie in wait — sometimes patiently for days — at a greater distance and likely as not he’ll cross, or crisscross his own trail in choosing his hiding place. As Johnny explained to me before I hunted my first buff, if there are any ground rules in hunting African big game you may be certain that the Cape buffalo will ignore them. No wild animal anywhere in the world is more unpredictable.

“Another thing; unlike the rhino, a buff has damned good eyesight. And that makes him hard to approach.

“If a buffalo herd is grazing out on the open plain there may be egrets riding on the backs of the animals and you can see them take to the air and fly around like sheets of white paper blown by the wind. According to Johnny, and I’ve never heard anyone with a different explanation, they pick off and eat the ticks and when they take to the air they alert the buffs to the imminence of danger, whether it be in the form of a human hunter or a lion.

“In bush, thicket or tall grass, even a large herd may move so quietly that you may not know it’s there.”

On one such memorable occasion, Alex was lunching in camp with John Fletcher and Temple-Boreham when a Masai herder arrived with word that a hunter in a safari a few miles away had wounded a big buff, which then quickly disappeared.

Fletcher and the game warden exchanged glances of concern. They were both aware that in addition to the safari, there were other Masai herders tending their cattle in the surrounding area. Temple-Boreham shook his head grimly.

“Mustn’t leave that buffalo on the loose. Likely to toss the hunter or a Masai. Perhaps both.”

They set right out to track the wounded buffalo, the game warden with the Masai, Alex pairing off with Fletcher.

Temple-Boreham and the herder took off in the direction where the buff had last been seen, found its trail, plainly marked by dripping blood, and followed it.

About an hour later they observed cattle far out on the sun-scorched plain beyond the brush. The game warden scanned the plain through his glasses but saw no sign of a moran, a warrior-herder.

At this point the trail led in the direction of a waterhole marked by a single moyela tree.

Suddenly the game warden froze in his tracks.

An instant later the wounded buff thundered out from behind the tree and charged.

The game warden was ready and brought the buff down with a brain shot.

He nodded toward the moyela. “That the gree where the buffalo was wounded?”

“Same tree,” the Masai answered. “Buffalo he wait at tree for hunter who shoot him.”

Temple-Boreham glanced again toward the untended cattle. “Guess you better look behind the tree,” he said quietly.

His companion moved forward. A few minutes later he shouted to the game warden: “Find moran here. Is pelele?”

What had happened here was plain to see. The herder had approached the waterhole, spear in one hand, goatskin water bag in the other. He had been unaware of the lurking buff until too late.

The buff had gored him terribly, punching an enormous hole in his belly, virtually degutting him before tossing him high in the air and snapping his spine like a dry twig. The horn of the Cape buffalo is broad at the base, averaging 12 inches. Despite this impressive thickness, it does not impale as it tapers sharply to the tip. The powerful upward thrust of the buff’s head when the horn pierces the body tosses the victim into the air, arms and legs grotesquely angled like a human swastika.

Alex Cord and Fletcher had left camp in another direction, planning to intercept the wounded buff if the game warden did not succeed in catching up with it. They hiked into the thick brush some distance beyond the waterhole, searching for tracks.

“As we hunted through the brush I gradually became aware that a lot of buffalo were somewhere in the vicinity,” Alex relates. “I could smell them and hear their movements, but I couldn’t see a single one of them.

“Suddenly I was confronted by a buff cow a short distance ahead of me. Behind her I could see the head of a calf. I guess that the cow figured I was a menace to her calf for she started toward me.

“I didn’t want to shoot her if I could avoid it and I started backing away. She came on faster. She lowered her head, getting set to charge me.

“At this point I turned and ran, if you can call a fast, frantic stumble running. The bush was so dense I knew I couldn’t fire an accurate shot if I had to. Johnny was awrae of my predicament but he wasn’t in any position to help and was reluctant to fire a snap shot for fear of hitting me.

“The cow was gaining on me, mowing down brush like an army tank.

“Johnny shouted to me to spook off which I was trying to do and I made for the nearest tree and tried to climb it. That tree bent under my weight like a green sapling. I dashed to another and when I grabbed it the same thing happened so I started running again with the cow snorting heavily behind me.

“There were no other trees nearby and I thought of a couple of things I had heard that guys did when caught in a similar situation.

“One supposedly peeled off his shirt, turned to face the charging buff and played it like a bull fighter with Veronicas and other tricks of the bull ring until another hunter maneuvered into a position to make a killing shot.

“Perhaps this can be done if a guy is agile on his feet and the terrain is right. But it is suicide to try it in thick brush where there isn’t enough clearance to swing a cat.

“The other tactic I’d heard about was to lie down and pretend to be dead. Some whites as well as the Masai, the Kikuyus and the Somalia believe that a buff will neither horn, toss nor trample upon a body he has not killed himself. But as Johnny had pointed out to me, a buff is the least likely to follow any ground rules and with this big cow coming after me I had no intention of putting the theory to the test.

“I just kept on running with the cow gaining on me at every step. Finally — it seemed like an eternity later — I heard the blast of Johnny’s Rigby and the cow dropped in its tracks.

“I came to a stop. Then I heard another animal approaching through the brush. It was the calf, following its mother. Luckily it was the only buff that did. I don’t know what happened to the rest of the herd. Apparently it had completely ignored what was going on and had moved off in another direction.

“We rounded up the calf and brought it back to the camp with us. Later, Lynn — that’s Temple-Boreham — took it somewhere out on the plain and released it to find its way back to the herd.

“There’s one thing more I want to add about Cape buffalo. Not only does it horn, toss and trample, but it has formidable teeth which can take a hellish bite and even its tongue, as raspy as a steel file, can inflict considerable punishment.

“From Mombasa to the Masai, Amboseli Game Reserve, I’ve heard grisly stories about the buff’s tongue. The most popular version is about a female hunter, name unknown. I’ve come across that story repeatedly, not only in Kenya but in popular books about African hunting and in ‘authoritative’ tomes about Cape buffalo, Syncerus caffer.

“There are even writers who claim that they knew and hunted with the ill-starred, anonymous lady.

“The way they tell it is that one day she started out from her safari camp to hunt alone, which is a rather idiotic thing to do in big game country.

“She was some distance from camp when she encountered a buff and fired at it with a double barreled .405.

“Her first shot hit the buff in the shoulder and infuriated it. Her second was a complete miss and the wounded animal charged. There wasn’t time for her to reload. She dropped her weapon and ran to the nearest tree. She managed to climb it before the buff got to her.

“The buff hit the trunk with a terrific impact but failed to knock her down. It tried to hook her by plunging upward but she clung to the branch just beyond reach of its lethal horns and drew her bare legs in bus shorts as high as she could.

“After making several more attempts to dislodge her, the buff switched to another tactic. It stretched upward as far as it could reach and licked her ankles. She was unable to pull her legs up any higher and the buff kept working on her ankles with its long, rough tonuge, through skin and flesh right down to the bone.

“Her white hunter didn’t find her until after daybreak the next morning. He shot the buff which was still standing at the tree and as he  approached he saw that she had strapped herself to the branch with her belt so that she would not be shaken down.

approached he saw that she had strapped herself to the branch with her belt so that she would not be shaken down.

“He called to her but she did not answer and when he reached the tree he discovered that she was dead. She had bled to death during the night and there wasn’t a strip of flesh remaining on the bones of her ankles.”

Upon returning to the U.S., Alex immediately became involved again in his acting career and months passed before he completed several movie and television commitments.

During this time he chance to hear about a little known and exciting kind of hunting that was going on in the West; roping and capturing mountain lions alive. The idea sounded intriguing and he resolved to investigate it.

In an interim between pictures he went to Canyon City, Colo., where he located a couple of chaps who were experts. With Alex Cord the result was inevitable. He relates his experience without dramatic embellishment.

“They briefed me about their technique and we went up into the mountains with a pack of trained hounds. Most of them were veterans of previous cat hunts with the scars that showed it.

“These hounds knew their business. They tracked a mountain lion to a high rock ledge where it was sunning itself and it took off in a series of bounds with the pack hell-bent in pursuit. I’d say that some of its jumps measured about 20 feet.

“The hounds treed it part way down the mountain slope and kept it up in the branches until we arrived. The cat was average, about 150 to 160 pounds, its lithe, six-foot body covered with tawny fur.

“When I looked up at the cat with its long, twitching tail, it seemed enormous.

“I’d learned to use a rope as a youngster back on the Wyoming ranch and I didn’t have much difficulty in getting a rope around its neck. From this point on the action was plenty fast.”

It took all of Alex’s strength to jerk the cat down from the branches. The cat landed on its feet, a snarling, screaming, furious feline.

Alex dashed for the tree, snubbed the rope around the trunk and hoped that the cat wouldn’t bite through it with its long murderous fangs. He had been warned that this sometimes happened.

The maddened cat tried to free itself by backing away from the tree, which kept the rope taut.

Grabbing a light, but bite-proof flexible wire cable, Alex maneuvered the loop so that he roped the cat’s left front foot and secured it to the tree trunk.

Leaping upward, twisting and turning with a ferocious display of fang, the maddened cat tried to get at Alex who was approaching again, readying a second wire loop.

He watched for an opening, darted forward, then to the side to dodge the cat’s kicking hind legs, threw the loop and missed.

On his next try he succeeded in catching the cat’s rear right foot. Sprinting to the tree he wound the second cable end around the trunk.

Although the mountain lion was now anchored fore and aft it fought more furiously than before when Alex flipped it with a powerful jerk on the cable. Its two untied legs lashed upward in frenzy, deadly claws fanning air in disemboweling arcs. Not until Alex succeeded in ropiong those two legs could the cat be approached, taking care to remain beyond reach of its terrible, snapping jaws.

“After tying up that cat,” said Alex in a succinct understatement of fact, “I understood why capturing mountain lions alive will not become a popular sport among hunters.”

On one of those rare days when Alex Cord was relaxing (he had just finished Stiletto for move producer Joe Levine), I asked him about his greatest hunting thrill.

“Elephant!” he answered without hesitating.

The story of how he bagged his elephant to put in proper perspective, begins out west in the ski resort area of Squaw Valley.

Alex had made arrangements for a safari with John Fletcher. Temple-Boreham and Gen. James H. Doolittle of WW II Tokyo-bombing fame.

A few weeks before he was scheduled to depart for Kenya he had a long free weekend so he flew to Squaw Valley to get in some skiing.

He was schussing down a steep trail when he had an unfortunate spill. For a skier to break a leg in one or two places of course is fairly common. But Alex set a record, as it was discovered when he was hurred to the hospital, by breaking his leg in six places.

His leg was still in a cast as the day neared for him to leave for Kenya. He stared pensively at the cast.

“What do you think, Doc?” he asked.

“Absolutely out of the question,” his physician said sternly.

So, with his leg in a cast, Alex flew to Kenya.

“Naturally that mending leg was a bit of a handicap on safari, but I had made the decision and I couldn’t very well complain. Especially with General Doolittle in the party.

“He was one great little guy. He was 72 years old at the time but he hiked 10 miles a day through the brush like a man half his age. he also had the most inquisitive mind of anyone I’ve ever known. Flora, fauna, natives, terrain formations; everything interested him greatly and his knowledge was amazing.”

Once there had been plenty of elephants in this section of Kenya. But day after day as Alex and Doolittle explored the aera surrounding their camp they became more and more appalled by the toll taken by poachers. They came upon carcasses, many of them near waterholes from which only the tusks had been hacked out.

“Wanton slaughter,” explained Temple-Boreham indignantly. “Gangs of poachers lie in wait at waterholes until elephants appear, then hit them with a barrage of poisoned arrows.

“We apprehend some of these scoundrels and confiscate the tusks which are sold at auction at the government’s ivory warehouse in Mombasa. But the poachers move around quickly from one district to another and the black market for ivory is increasing. Arrest one gang of poachers and there’s always another ready to replace it. The battle is endless.”

Late one afternoon, just before sunset, Alex and John Fletcher came upon fresh elephant tracks and the white hunter examined them carefully.

“Looks like this one is yours,” he nodded, “but it’s almost dark, so we’ll wait until morning.”

They returned at 6:30 a.m. the next day and began tracking through fairly open country. It soon became apparent that the elephant wasn’t loafing in the immediate area but was definitely headed somewhere.

For the next two hours as they hiked they occasionally encountered pungent-smelling elephant droppings that swarmed with small forest flies. Once Fletcher stopped to study one.

“Kernels of undigested maize. This elephant probably trampled through a maize field recently, was driven off and is now looking for another field to raid.”

They resumed trailing with Fletcher setting a steady pace. Alex was beginning to tire and his bad leg was aching. he didn’t mention it lest Fletcher decide to call off the hunt.

The trail now led them into the brush and the walking became tougher. Wait-a-bit thorns and creepers pulled at their legs, sometimes snarling them and Alex’s injured leg developed a steady pain. He was grateful when they emerged into an open clearing under a canopy of bright blue sky.

Midway across the clearing Fletcher came to an abrupt stop and pointed toward the tangled brush beyond.

“Elephant’s in there watching us. You can see his head over there toward the left.”

Standing in the sunlight, Alex scanned the bush shadows and glimpsed the head of their quarry for a moment before it retreated deep into the thicket.

“The sight of that head looming up in the bush made me forget my aching leg,” he said. “It sure excited me.”

“The bush was too thick to go in after it. We had to wait for it to come out and Johnny was certain that it would, sooner or later.

For the next hour or so the elephant played hide and seek with us. We caught an occasional sight of it at the edge of teh clearing, first at one spot, then another. I guess it was waiting for us to go away and was getting madder each time it saw us still in the clearing. Each time it retreated back into the bush I marveled at how lightfooted an elephant can be in moving around. I’d heard buffalo and other animals signal their movements but this big fellow moved from point to point in comparative silence until it finally decided to charge us.

“When it did, it thundered out into the clearing and it looked like it was about 100 feet tall. Its high-pitched shrieks of rage were siren-loud; ears cocked and trunk up.

“This time I didn’t wait for Johnny to tell me to fire. The distance from the edge of the clearing to where we were standing was short and the elephant was coming toward us at terrific speed.

“I knew that if I missed there wouldn’t be time for Johnny to fire before the elephant trampled us; that he was gambling his life to give me this chance. I had to stop that elephant fast, either with a shoulder shot or with a bullet in its wide open mouth. A forehead shot, what the pros call a ‘duffer’s shot’ wouldn’t stop it. Johnny had explained to me that the top part of an elephant’s skull houses little more than air cells and a lot of amateur big game hunters have been killed after mistaking this for the brain.

“I aimed at the redness of the open mouth and fired.

“The impact of the .470 slug was so great it killed the elephant in mid-stride. Its forefoot didn’t even touch the ground. It tumbled forward in a half-somersault and fell dead in a huge heap.

“My heart was pounding wildly and I don’t mean this to sound dramatic. It kept right on pounding and I think it was about 24 hours before my excitement subsided and I returned to normal.

“My greatest hunting thrill? That was it. Anything else would be an anticlimax after bagging that elephant.”

This explains why Alex Cord no longer has much interest in hunting big game with a rifle. He’ll continue to go on African safaris whenever he has the opportunity, but hereafter he intends to do his shooting with a camera.

This explains why Alex Cord no longer has much interest in hunting big game with a rifle. He’ll continue to go on African safaris whenever he has the opportunity, but hereafter he intends to do his shooting with a camera.

“Hunters can still bag limited game quotas in designated ‘shooting blocks’, but nine out of every 10 who now go on safari in Kenya obtain their ‘trophies’ on film,” he says.

“There are excellent subjects to be photographed everywhere, from colorful concentrations of lesser and greater flamingos at Lake Nakuru to 18 foot tall reticulated giraffes in the Marsabit Game Reserve.”

From now on, that’s for Alex Cord.

A Secret From My Airwolf Days…

This isn’t a well known fact…. I have starred in a video game and I would like to share it with you. Now… If you bought this game I would like to hear from you… For the rest of you oblivious to my 80’s video game fame… Here’s a YouTube video that will let you see me in a different light. I ran across a post earlier from Andy Hogue showing a pixelated version of… ME! I just had to find this game. Who’s up for a trip to the games arcade later? I demand the right to play as Archangel! LOL!

Get Your Alex Cord E-book Autographed!

Who wants an Alex Cord autograph?

There’s a new and exciting event to share with Alex Cord fans all over the world. Alex can now autograph E-book copies of his books for you… That means you can have a personal autograph from Alex Cord on your E-book within moments! All you need to do is purchase a copy of “Days of the Harbinger” or “A Feather in the Rain” as a Kindle E-book and then head over to authorgraph to get your E-book signed by the man himself! This is just one of many new exciting things we are doing to try and bring Alex closer to his fans…

A Conversation With Alex

Alex Cord movie star, author, horseman, scriptwriter, progressive jazz fan and rancher is shown here in a candid interview from 2004. This little known interview lets you right into the life of one of Facebook’s newest trendsetters. Over the last couple of weeks Alex has seen his Facebook following continue to grow, book sales rise and has become a followed and respected member of the Twitter community.

This interview will be the first of many we will be posting over the next few weeks. Interviews are said to be an entry into the soul of a person– so for Alex Cord fans these interviews should prove to be interesting and revealing in ways no previous Alex Cord interviews have. This interview has had very little attention over the years and I thought it would be a good one to share with you all. Thank you for taking the time to come over and read it! Okay, so lets roll with Alex and see what he has to say about movies, movie stars, writing and life itself.

Q: If you were offered a series now, say a modern-day western, would you do it?

Q: If you were offered a series now, say a modern-day western, would you do it?

AC: Yes. I would do a series now if it were something that appealed to me. Most of the things I’m offered do not hold any charm for me. Television is a wasteland for the most part. I like writing because I am not depending on anyone else. It is all me. It is hard work and always challenging. You sit and stare at a blank page until drops of blood appear on your forehead.

Q: Have you stayed in touch with any of the fellow actors you’ve worked with down through the years?

AC: Yes. Kirk Douglas and I have remained friends over the years. We see each other periodically. Ernie Borgnine is a dear man, a good friend and a consummate pro. We also share a passion for good Italian food that we prepare ourselves. I was recently at a surprise party for his eightieth birthday. God bless him. Bob Fuller (Dr. Brackett, Emergency!) is one of my very best friends. A finer man, this spacious world cannot again afford. And there are many others. Actors are very special people. It takes great courage, tenacity, and faith to commit to being an actor. The odds against one making a living at it are enormous.

Q: What would you say is the greatest accomplishment in your professional life?

AC: I don’t think there is a “great” accomplishment in my professional life, not yet anyway. Perhaps when “Feather” is published (now available here) I will feel some sense of accomplishment.

Q: Is there a chance we will ever see ‘Harbinger’ (now published and on sale through Timber Creek Publishing) in print? Or Trellium (Sandsong, Alex’s first novel) as a movie?

AC: The Harbinger is in very rough shape and needs a lot of work. I’m still very much intrigued by the idea of a hoax on such a grand scale but I have other projects that are higher in priority. Trellium (Sandsong) is a beautiful love story and has been optioned five times by film makers who have not been able to put it together. I have every confidence that it will happen. It’s simply a matter of the right people coming together. Some of the best films that have ever been made have been the most difficult to mount and taken the longest time to do it. “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” took fifteen years from the time it was first bought until it made it to the screen.

Q: What would you say is your great accomplishment as regards your personal life?

AC: In my personal life, I think staying alive for as long as I have is pretty good. When I was very young I thought that there was something glamorous about being convinced that I would not live to be thirty. Now, I think it would be glamorous to live to be a hundred, as long as I could still get around without dribbling on myself, and not be a burden to anyone.

Q: If you could go back and do it all over, would you do anything differently and if so, what?

AC: I would not have married at the tender age of 21. Other than that I don’t think I’d want to do anything much differently than I did. Of course I do wish I’d been smarter, better educated, and kinder and gentler to others. More tolerant, more forgiving. I work on that every day. I’ve had a great variety of experiences that most people don’t even dare to dream about much less live them. Most of my dreams and fantasies have come true. If I had more than one life to live then there are many things I would do other than what I’ve done in this one. I would study veterinary medicine, be an archaeologist, work with wild animals in Africa and pray that I would have the treasured gift of a musical talent.

Q: Are you more comfortable with your horses or with people?

Q: Are you more comfortable with your horses or with people?

AC: I love all horses. Well, mostly all. I wish I could say the same thing about people. Those that I love, or even like, I am passionate about. Those that I don’t like, the blunders that never should have occurred, give rise in me a total lack of tolerance. Somebody once said, “One should forgive one’s enemies, but not before they are hanged.” I like that.

Q: Will you list some of the charities you have been involved with?

AC: As captain of the Piaget Chukkers for Charity Polo Team for 5 years and 13 years of competing in the Ben Johnson pro/celebrity Rodeos for charities, I had the opportunity to work with many charitable organizations. The March of Dimes, Muscular Dystrophy, Cystic Fibrosis, the “Roundup for Autism” in Texas, The Shriners Children’s Hospital, a Cancer Treatment Center in Oklahoma, therapeutic riding programs for the handicapped, a great one called “Ahead With Horses.” It is a very rewarding, humbling and fulfilling thing. It enrichs the soul.

Q: What was the most rewarding acting role you ever did and why?

AC: A play I did on the London stage with a wonderful and famous Irish actress named Siobhan McKenna was called “Play With A Tiger.” I was nominated for the Best Actor Award by the London Critics. The other nominees were Christopher Plummer in Becket and Albert Finney in Luther. Christopher won but to have been nominated with such illustrious company was a great honor. The part was an actor’s dream.

Q: What was the most fun role you ever did and why?

AC: I played a cop posing as a homeless derelict. A great opportunity to create a character wherein I was totally unrecognizable. Spent a lot of time studying, observing those poor desperate people.

Q: What do you want other people to remember you for?

AC: I’d like it if people would say, “He was a kind man, honest, courageous, cared about other people, and always rode a good horse.”

Q: Are you happy with the way things turned out for you in this life?

AC: I am not happy about losing my son. I believe it is the worst thing that can happen to a human being. The pain never leaves and the vacancy is never filled. It is with me every moment of every day. I would like to have had a cohesive, loving, lasting family. And yet there is a very real part of me that has always wanted to ride off into the sunset and seek the next unknown adventure.

Q: What advice would you give to someone following in your (acting) footsteps?

AC: Don’t become an actor unless everyone tells you that you should not, and yet you are compelled to do it anyway. And never give up.

Q: What’s your basic philosophy of life?

AC: Dream. Follow your dreams without fear. Ride a good horse, and keep him between you and the ground.

Q: What does Alex Cord really want out of life — right now — and what did he want earlier in his career? Did you achieve everything you’d hoped to?

AC: The only thing I know for sure is that I am far too complex a person for someone as simple-minded as I am to understand.

Q: Do you have any pearls of wisdom you’d like to impart before closing?

AC: Whatever their other contributions to our society, lawyers could be an important source of protein. Seek wisdom. Just because you think something is true today doesn’t mean it will be true tomorrow. Never stop learning. Adios.

Genesis ll

Friends,

Surfing through the world of YouTube I just found something special. A clip from “Genesis ll”. This was a pilot created by Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and directed by John Llewellyn Moxey. The film, which opens with the line, “My name is Dylan Hunt. My story begins the day on which I died”, is the story of a 20th-century man thrown forward in time, to a post-apocalyptic future, by an accident in suspended animation.